The Origins and History of Mochi

・Mochi has been a part of Japanese life since ancient times.

With the spread of rice cultivation, people began steaming rice and pounding it with a mortar and pestle to make mochi.

・By the Nara period (710 AD), records show that mochi was already used as an offering to the gods.

The Sacred Meaning of Mochi

・Mochi was considered a “source of strength” and was offered to the gods on special occasions.

・Kagami mochi, displayed at New Year’s, is offered to the Toshigami (the deity of the New Year). Afterwards, it is shared among family members to receive divine blessings.

・Because mochi stretches well, it symbolizes longevity, prosperity, and good fortune for the household.

Mochi as Culture

Festive dishes: ozōni (New Year’s soup with mochi), hishimochi (diamond-shaped mochi for Hinamatsuri), kashiwa mochi (oak-wrapped mochi for Boys’ Festival).

Celebrations: Red-and-white mochi is distributed at weddings or house-raising ceremonies, believed to ward off misfortune.

Regional differences: Round mochi is common in Kansai, while square mochi is preferred in Kanto. These differences arose from preservation methods and symbolic meanings such as “harmony” in round shapes.

How Mochi Is Made

Selecting glutinous rice (mochigome)

Mochi is made from special glutinous rice, not regular table rice.

It has a sticky texture and elasticity that makes it suitable for pounding.

Washing and soaking

The rice is thoroughly washed to remove dirt and debris.

Soaking for 6–12 hours allows the rice to fully absorb water, resulting in a softer texture when steamed.

Steaming

The soaked rice is steamed in a wooden steamer or pot.

It is steamed for 40–60 minutes until translucent and soft enough to be crushed with fingers.

Mochitsuki(Pounding)

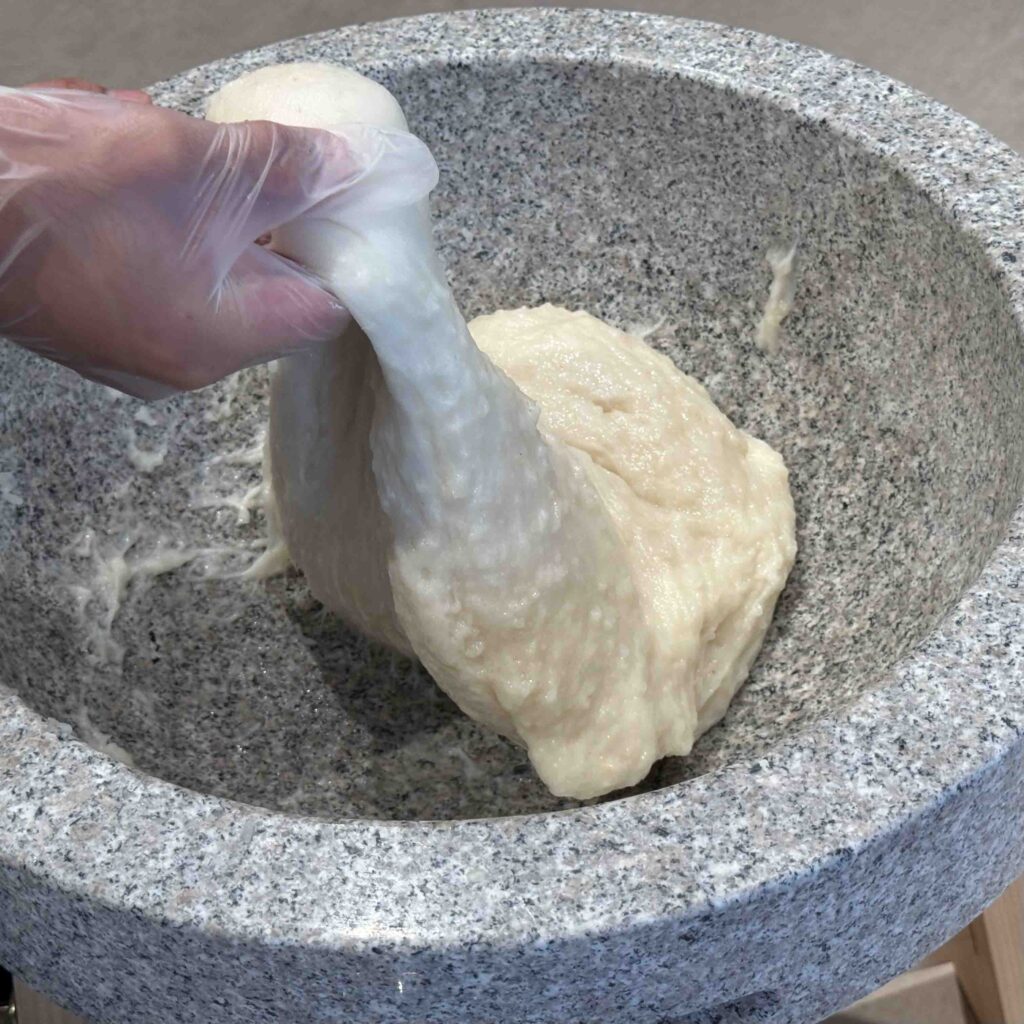

The steamed rice is placed in a mortar (usu).

At first, the rice is gently kneaded with the pestle (kine) to crush the grains.

As it binds together, the rice is pounded vigorously with rhythmic shouts of “Yoisho!”

The “turner” quickly folds the rice between strikes, creating an even, stretchy texture.

Repeated pounding produces the familiar chewy, elastic mochi.

Shaping

The finished mochi is divided and shaped into round balls or pressed into molds to make sheet mochi.

Hands are dusted with water or starch to prevent sticking during shaping.

Varieties of Glutinous Rice

Different regions of Japan cultivate their own varieties of mochigome, each with unique stickiness, texture, and flavor.

Famous types include:

- Mangetsu Mochi

- Kogane Mochi (Niigata Prefecture)

- Hiyokumochi (Kyushu region)

At Hanbei, we use Mangetsu Mochi.

Features of Mangetsu Mochi

A premium variety once offered to the Imperial family. Grown mainly in Ibaraki Prefecture, it has a distinguished history—Emperors once planted it in the Imperial rice fields.

Strong stickiness and elasticity. When made into mochi, it produces a smooth, chewy texture with excellent resilience.

What Is Mochitsuki?

Mochitsuki is the traditional Japanese ceremony of pounding steamed glutinous rice with a mortar and pestle. At New Year’s and other celebrations, people gather, chant in unison, and pound mochi together. Beyond food preparation, it symbolizes community bonds and prayers for abundance.

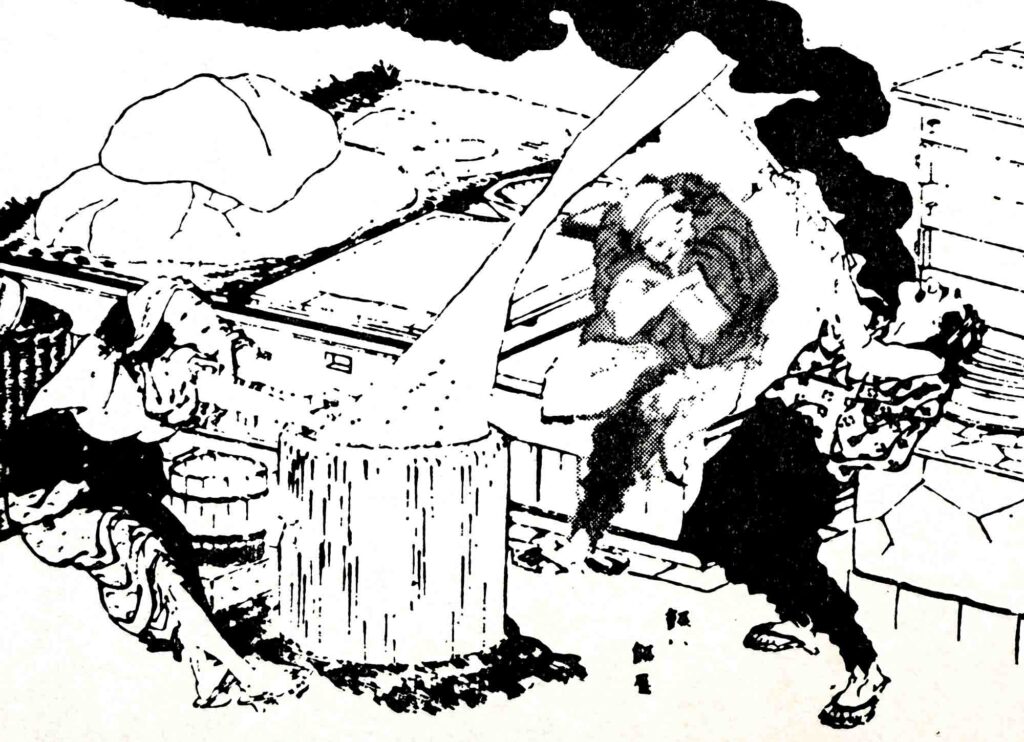

From a folkloric perspective, mochi pounding has also been interpreted as a metaphor for the union of male and female. The mortar (usu) represents the feminine, while the pestle (kine) symbolizes the masculine. Their rhythmic interaction has long been associated with fertility and the cycle of life.

Thus, mochi pounding is not only a culinary practice but also a symbolic ritual, deeply rooted in Japanese culture as a prayer for vitality and prosperity.

Tools of Mochitsuki

Mortar (Usu)

A large vessel, usually made of wood or stone, used to hold steamed rice while it is pounded. Symbolically, the usu represents the feminine, embodying receptivity and fertility.

Pestle (Kine)

A heavy wooden mallet with a long handle, used to pound rice inside the mortar. Symbolically, the kine represents masculine strength. Together with the usu, it produces life-giving mochi.

Water for the “turner”

In addition to the pounder, the “turner” plays a crucial role. With wet hands or a ladle, the turner folds the rice between strikes to ensure it is evenly pounded. The harmony between pounder and turner results in smooth, beautiful mochi.