- 1. What Is Shodō?

- 2. The Four Treasures of Calligraphy (文房四宝, Bunbō Shihō)

- 3. The History of Shodō in Japan

- 4. Major Styles of Calligraphy

- 4.1. 1. Oracle Bone Script (Kōkotsubun)

- 4.2. 2. Bronze Script (Kinbun)

- 4.3. 3. Seal Script (Tensho)

- 4.4. 4. Clerical Script (Reisho)

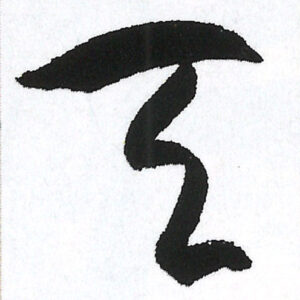

- 4.5. 5. Cursive Script (Sōsho)

- 4.6. 6. Semi-Cursive Script (Gyōsho)

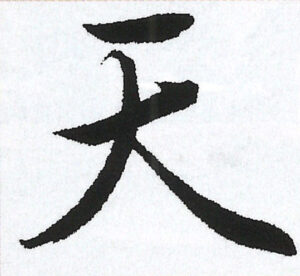

- 4.7. 7. Standard Script (Kaisho)

- 5. Why Shodō Flourished in Japan

- 5.1.1. Historical Roots

- 5.1.2. Education

- 5.1.3. Spiritual Discipline

- 5.1.4. Artistic Expression

- 5.1.5. Part of Daily Life

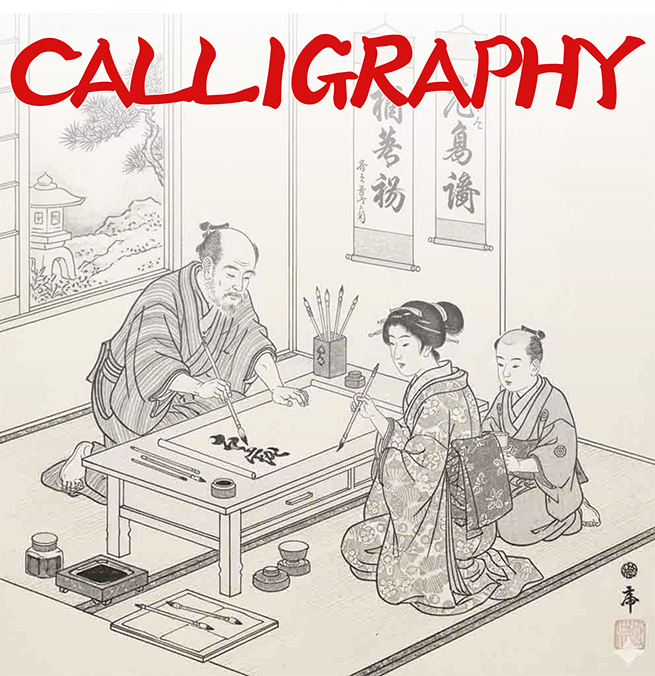

What Is Shodō?

The Traditional Japanese Art of Writing with Spirit

Shodō (Japanese calligraphy) is more than just the act of “writing.” It is an art form unique to Japan, where brush, ink, paper, and the calligrapher’s spirit become one. Through this union, characters are infused with life, expressing not only meaning but also the writer’s inner world and aesthetic sense.

Shodō is not limited to the beauty of letterforms—it embraces the rhythm of brush strokes, the contrast of thick and thin lines, the depth of ink tones, and the harmony between characters and empty space. Together, these elements create an infinite world of artistic expression.

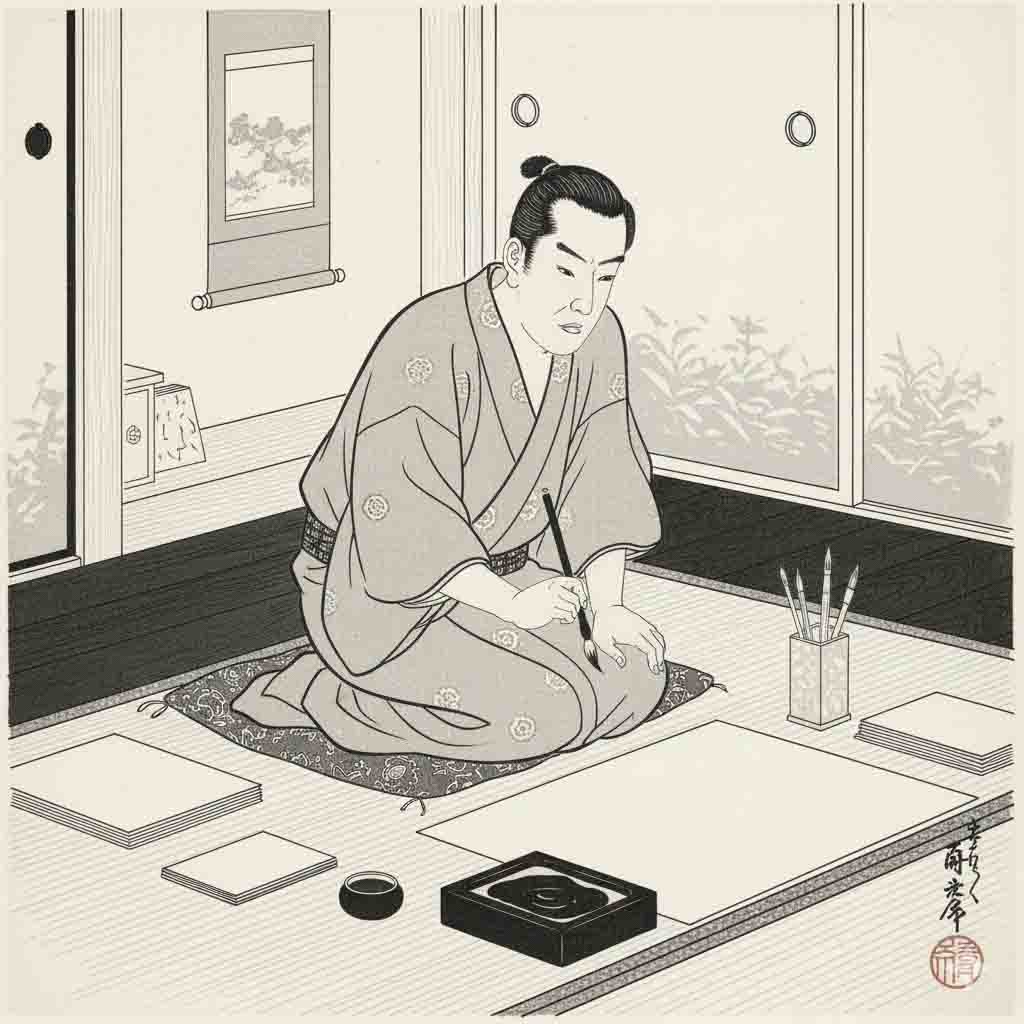

The Four Treasures of Calligraphy (文房四宝, Bunbō Shihō)

The four essential tools of shodō are known as the “Four Treasures of the Study,” each contributing deeply to the spirit of the art:

- Brush (Fude): Made from animal hair, it conveys the breath and heart of the writer onto the paper.

- Ink (Sumi): Traditionally made from soot bound with natural glue, producing shades of black that give depth and vitality to the writing.

- Inkstone (Suzuri): A stone slab used to grind the ink stick with water. Its quality directly affects the richness and beauty of the ink.

- Paper (Kami): Often handmade washi paper, whose texture, absorbency, and softness create unique expressions such as blurring and fading.

The History of Shodō in Japan

The history of Japanese calligraphy begins with the adoption of Chinese characters and evolved into uniquely Japanese styles through the creation of kana.

Chinese characters (kanji) were introduced from the continent.

With the spread of Buddhism, sutras were copied, and written culture became rooted in Japan.

Man’yōgana (an early phonetic use of Chinese characters) was employed in works like the Man’yōshū, laying the foundation for Japanese writing.

The birth of kana and the establishment of Japanese calligraphy

With the end of official missions to China, a distinctly Japanese culture blossomed.

Kana scripts (hiragana and katakana) emerged, derived from simplified Chinese forms, revolutionizing written Japanese.

Elegant Wayō (Japanese-style calligraphy) flourished, led by masters such as the “Three Brushes” (Kūkai, Emperor Saga, Tachibana no Hayanari) and the “Three Great Calligraphers” (Ono no Tōfū, Fujiwara no Sari, Fujiwara no Yukinari).

The Rise of the Samurai and the Influence of Zen Buddhism

The rise of the warrior class favored a more vigorous and simple style.

With the spread of Zen Buddhism, calligraphy by Zen monks was highly valued, emphasizing spiritual strength.

Popularization among the common people and the birth of various schools of calligraphy

Widespread literacy through temple schools made calligraphy common among the general population.

New calligraphic styles arrived from China and blended with Japanese traditions, giving rise to diverse schools of calligraphy.

Establishment as an art form and modern calligraphy

Calligraphy became part of school education, and remains so today.

Beyond traditional forms, avant-garde calligraphy (zen’ei shodō) emerged, breaking away from conventional script to expand calligraphy as a modern art form.

Major Styles of Calligraphy

Over centuries, six (plus one) principal script styles were developed, each with distinct beauty:

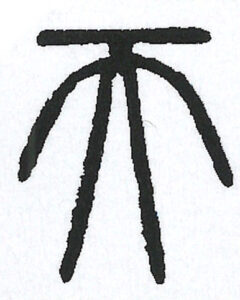

1. Oracle Bone Script (Kōkotsubun)

The earliest form of Chinese characters, carved on bones and turtle shells around the 14th century BCE.

2. Bronze Script (Kinbun)

Characters cast on bronze vessels during the Yin and Zhou dynasties, with fuller, rounded strokes.

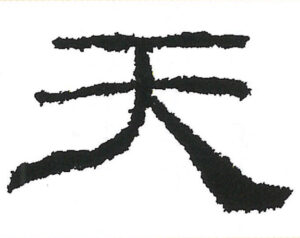

3. Seal Script (Tensho)

The standardized script of the Qin dynasty, characterized by graceful, straight lines; still used for seals today.

4. Clerical Script (Reisho)

A simplified script from the Han dynasty, notable for its horizontal flow and “wave-like” brushstrokes.

5. Cursive Script (Sōsho)

A highly abbreviated, flowing style suited for speed writing, with characters often linked together.

6. Semi-Cursive Script (Gyōsho)

Between standard and cursive, combining readability with elegance; widely used in daily life.

7. Standard Script (Kaisho)

Developed from clerical script, with clear, precise strokes; used as the foundation for study and practice.

These scripts influenced one another, reflecting historical shifts, and together shaped the depth of calligraphy as art.

Why Shodō Flourished in Japan

Shodō remains widely practiced in Japan for five main reasons:

Historical Roots

The blending of Chinese kanji with Japan’s own hiragana and katakana created a unique art form, deeply tied to Japanese literature and aesthetics.

Education

Calligraphy is a compulsory subject in schools, ensuring that every Japanese child experiences it. This builds awareness of writing beautifully and instills cultural values.

Spiritual Discipline

Practicing calligraphy enhances focus, corrects posture, and calms the mind. The act of grinding ink and concentrating on each stroke embodies Zen-like mindfulness.

Artistic Expression

Calligraphy is an expressive art, reflecting the calligrapher’s individuality. Variations in brush pressure, ink tones, and composition allow limitless creativity. Modern avant-garde calligraphy further broadens these possibilities.

Part of Daily Life

Calligraphy remains present in everyday traditions—New Year’s kakizome (first writing), handwritten greetings, envelopes, and ceremonial writing. Beautifully written characters convey respect and sincerity.